The core of game design is this article: While brainstorming and idea generation are enjoyable processes, they are only the beginning. Creating prototypes, testing them, iterating, and repeating are the majority of the tasks involved in game design.

Ensuring the game is balanced, interesting, functional, and intuitive is the aim of playtesting and development.

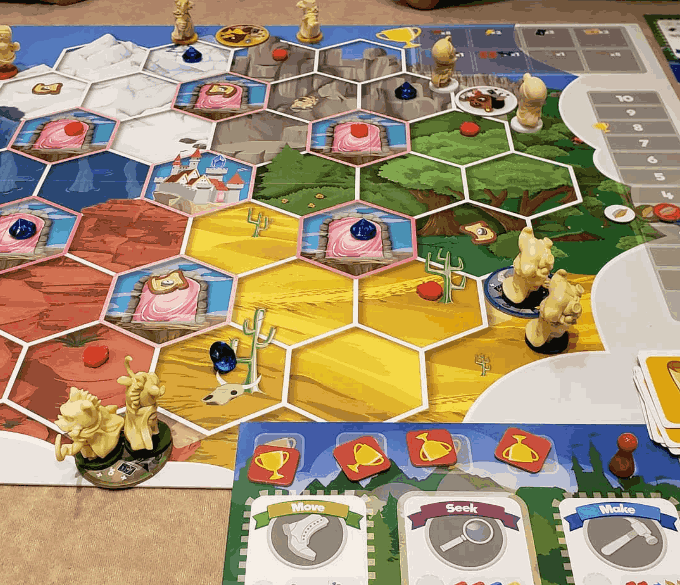

Playtesting and Early Prototyping

Minimum viable product, quick prototyping, and early expectations: In my initial effort, I aim to create a game that is just slightly complicated enough for me to play. In other words, I don’t design every single card in a game I plan to have 100 of because I know the game will probably alter a lot over time. Alternatively, I might create 10–20 cards, which would be sufficient for the game to play.

Tools: I create files in InDesign, print color documents with an HP Laserjet 200, cut cards with a Cutterpillar, and have a ton of extra tokens that I’ve accumulated over the years.

I occasionally conduct my own playtests, especially before I’m certain the game works at all. While I benefit most from having other human players at the table, I can work through the major kinks by myself before putting anyone else through an early prototype.

Playtesting Locally

I watch for happy, frustrated, or confused moments. Occasionally, I also frame the playtest around my goals and the state of the game at the time.

I would rather play than just watch. Though opinions on this matter vary among designers, I find that attending local playtests also helps me learn the most.

Let edge cases, but once you locate them, stay away from them: Playtesters are always appreciated when they discover a bug or weakness. However, once they’ve shown it, the playtest will no longer benefit from them continuously using the flaw to destroy their rivals; if they can’t seem to quit, I’ll take the aspect out of play.

I make a lot of notes during a playtest (I’m always shocked when a designer doesn’t), and then I put them away for a day to give me some space before I sit down to analyze the results and make the necessary adjustments.

Solo Playtesting

The easiest and fastest way to test your game is by playing it alone. Try the game as every player in this playtesting.

This is a quick and easy way to check for text legibility, ergonomics, and game-breaking mechanics, but it won’t help you make groundbreaking discoveries because you’re not testing your mental model of the game against someone else’s.

Quick Playtests

You don’t want to wait long between playtests, yet organizing a comprehensive playtest can be difficult. Having close friends or relatives test your game is nice. It’s still a good test to find problems and improve flow and dynamics, even if your friends and family know the game.

A rapid playtest allows you to change the rules mid-game, quit and start afresh, or start mid-game to test certain conditions or mechanics. Be less strict overall. This is not advised for formal playtests.

Guided Playtesting

A full playtest is recommended once your game is complete. During the game’s design phase, the designer should be there to explain the rules and clear up any confusion. Normal usability test etiquette applies. Allow players to make mistakes, ask about their rule knowledge, and never instruct them how to play “the right way”. The designer should set the setting and then go, only making tweaks and clarifying rules as needed.

Extreme Playtesting

After the game is determined, playtesting is about refinement. Extreme playtesting is necessary for testing the game for ludicrous, out-of-the-box play styles. We want to find ways player interaction can break the game and prepare for play styles we never considered. Monopolizing a resource kills the economy for everyone. Someone who avoids opponents. We want to find out how unexpected behavior makes the game unenjoyable and then create strategies to mitigate certain playstyles.

Playtesting Blindly

Late in development, blind playtesting is done. We give players the game and rulebook to figure out. No matter what, the designer should watch the game grow. The rulebook is tested since the game should be substantially finished. We can’t transport a designer with each box, so users must comprehend the game themselves.

You Alone

Playtesting usually begins with you testing various game pieces to determine if they operate. You may conduct a lot of testing in your thoughts by playing out possible actions and scenarios to determine which are interesting and which are open to players.

You can then play against yourself. Play the roles of the other players at the table and pretend you don’t know their cards.

Start by testing the game on yourself so you don’t waste anyone’s time if it’s a disaster. In my early days, I requested friends to assist me test a concept before playing it alone, and it was dreadful. Friends were unwilling to help me test other games after that.

Family and Friends

Friends and relatives are a terrific way to test a game after it works. These folks should want you to succeed, thus they should be willing to try your game.

They may not intend to damage you, so take their advice with a grain of salt. Watching their body language during the game is better than hearing their post-game thoughts.

Other Game Designers

Other designers can test your game and provide you with vital feedback on how to enhance it. Designers see games differently than average players and may be able to help you solve issues that regular gamers can’t.

Consider game designer feedback with suspicion. Designers often provide comments based on their vision for the game, which may not align with expectations.

If a game designer plays your game, playtest theirs too. Correct game design etiquette.

Strangers

After the game functions well, it’s time to release it, and the best method to gather honest feedback is to have strangers or friends play it.

Game stores, conventions, game design conventions like UnPub and Protospiel, and Facebook groups like the Board Game Design Lab community are great venues to locate playtesters.

Last Words

Playtesting could be difficult, but it doesn’t have to be difficult to recruit volunteers. You can use any of the aforementioned recommendations. If you provide a compelling incentive for people to play-test your game, you might be amazed at how insightful their comments can be!